Helmut Lang’s influence has always operated in a register that feels both understated and unmistakable. Across the years 1986 to 2005, working between Vienna, Paris, and New York, he developed a language that resisted spectacle and questioned the rituals through which identity is constructed, displayed, and consumed. The MAK exhibition “Séance de Travail 1986–2005” built from the museum’s extensive Helmut Lang Archive, donated by the artist in 2011, attempts the first comprehensive reconstruction of this period. Rather than staging a conventional retrospective, the exhibition turns the archive into a thinking system, a way to understand the structures that underpinned Lang’s fashion years and the cultural shifts they set in motion.

Central to this reevaluation is the séance de travail, the working method Lang introduced in 1988. Instead of the classical elevated runway, Lang presented his collections in raw industrial spaces where models, collaborators, and friends moved freely through the environment. The presentations dissolved the boundary between backstage and stage and merged menswear and womenswear in an unfiltered, dynamic rehearsal. At the MAK, these sessions reappear as life-size video installations that restore their physical immediacy. They read not as historical documentation but as experiments in how clothing behaves in relation to space, sound, and real bodies. They serve as reminders that Lang was less concerned with theatrical performance than with presence itself.

Lang’s aesthetic emerged against the backdrop of the late 1980s, a period saturated with glamour and excess. His response was a cooler and more media-conscious sensibility. With his debut L’Apocalypse Joyeuse, presented in 1986 at the Centre Pompidou’s exhibition Vienne, Naissance d’un siècle, he established the principles that would define his work: gender-spanning silhouettes, modular construction, and a refusal of ornamental logic. He combined streetwear, subcultural references, folkloric fragments, and eveningwear into a coded uniform for a generation of creatives who viewed fashion as a tool for sharpening identity rather than advertising it. What later became associated with minimalism in fashion was, in Lang’s case, a deeper commitment to clarity and psychological precision.

Technological experimentation played a significant, if understated, role in Lang’s career. In 1998, he became the first designer to premiere a runway show online, distributing CD-ROMs instead of front-row invitations. That same year, New York’s taxi tops carried more than a thousand advertisements for his campaign imagery, two of which survive in the MAK collection, including one featuring a photograph by Robert Mapplethorpe. A year later, by presenting his Spring Summer 1999 show in early September, and therefore before the European season, he unintentionally reshaped the global fashion calendar. These choices were not framed as revolutions, but they quietly reconfigured the systems through which fashion circulated.

The physical environments associated with Lang’s work further reinforced his sensibility. Developed with architect Richard Gluckman, the stores on Greene Street in New York and Rue Saint-Honoré in Paris avoided retail theatrics in favor of stark functionality. Site-specific installations by Jenny Holzer and Louise Bourgeois expanded these spaces into intermedia environments in which clothing, architecture, and text coexisted without hierarchy. At the MAK, the reconstruction of these elements allows fixtures and architectural features to be read as sculptural objects that illustrate Lang’s refusal to separate fashion from other forms of cultural production.

Collaborations were integral to Lang’s methodology. His partnership with Holzer began at the 1996 Florence Biennale, where he contributed a scent to accompany her text installation. In 2000, a conceptual perfume campaign replaced traditional product photography with Holzer’s declarative statements, an early example of communication that privileged intimacy and psychological charge over aspiration. A 1998 exhibition at Kunsthalle Wien, linking Lang, Holzer, and Bourgeois, marked the beginning of a sustained dialogue that extended into installations, scent, and product design. These were not collaborations in the contemporary branding sense, but intersections between practices grounded in shared conceptual concerns.

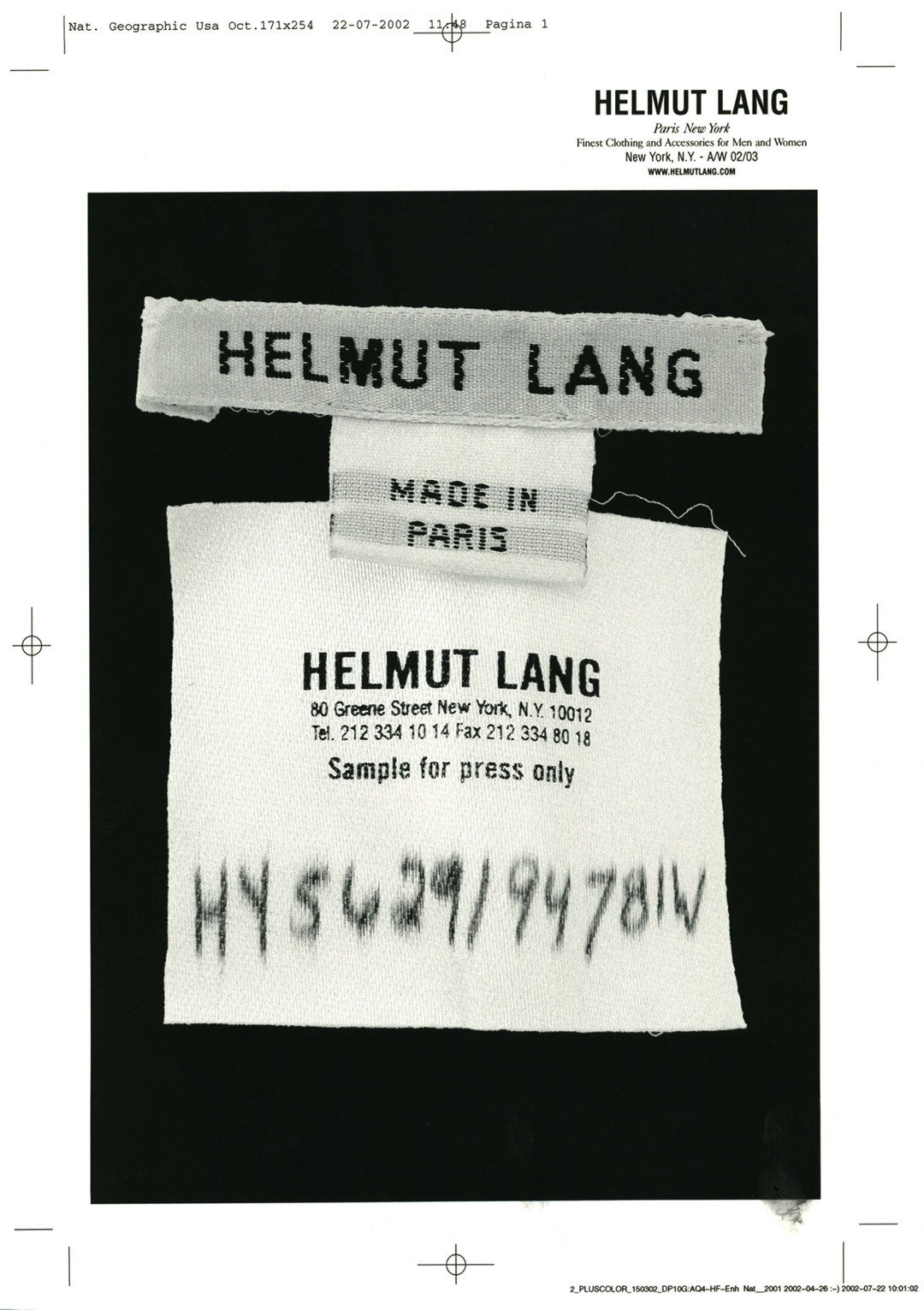

Lang’s communication strategies further challenged fashion’s own mythology. His photographs and campaigns embraced transparency, spontaneity, and the aesthetics of the unfinished. Backstage scenes, fittings, and the labor of production were brought into public view, collapsing the distinction between the polished and the incidental. This sensibility, now common across creative industries, was for Lang an argument for authenticity not as performance but as structure.

| MAK Helmut Lang Archive

At the center of the exhibition is the MAK Helmut Lang Archive, which contains more than ten thousand items spanning garments, prototypes, design drafts, advertising proofs, packaging, audio and video recordings, polaroids, lookbooks, and internal documentation. Guided by Lang’s belief that “all has equal weight,” the archive treats garments and ephemera as part of a cohesive conceptual system rather than separate categories. For the exhibition, a new review of the archive has revealed previously unseen materials, including full-length color video documentation of the séance de travail presentations with their original soundtracks. This is the first time these recordings appear publicly in their entirety. The result is less an archival survey than a reactivation of a practice structured by experimentation, refinement, and renewal.

What becomes clear throughout the exhibition is that Lang’s legacy cannot be reduced to a historical aesthetic or a nostalgic return to the 1990s. His work demonstrates how fashion can function as a mode of thinking that is interdisciplinary, precise, and attentive to the social conditions that shape visibility. Between 1986 and 2005, Lang reorganized the terms through which clothing engages with identity, culture, and technology. The MAK exhibition does not canonize his work as a finished chapter, but rather offers a lens to reconsider the systems he disrupted, the ideas he articulated, and the space he left behind. In that space, his work continues to serve as a point of orientation for understanding how creativity operates within, and sometimes against, the circumstances that define its moment.

On view at MAK Museum of Applied Arts, Stubenring 5 1010 Vienna, Austria through May 3rd, 2026.

Photos: Courtesy of MAK Museum

www.mak.at/exhibition/helmutlang

@mak_vienna